Living on a prehistoric island

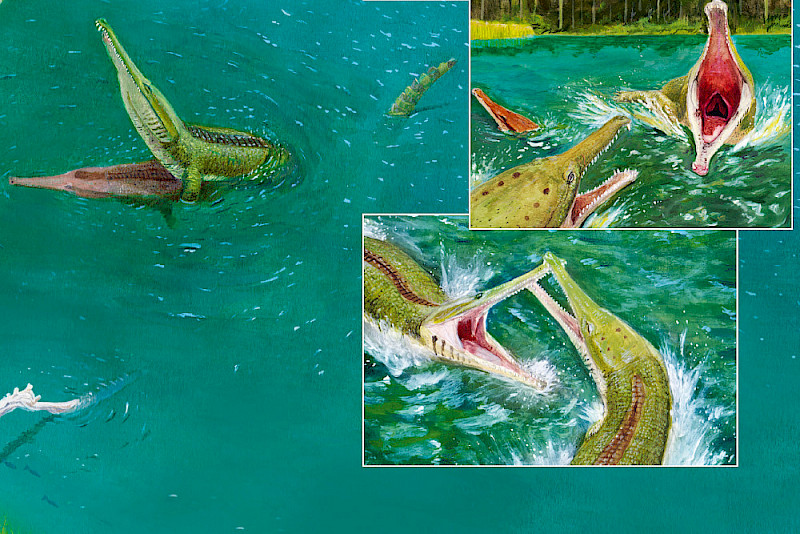

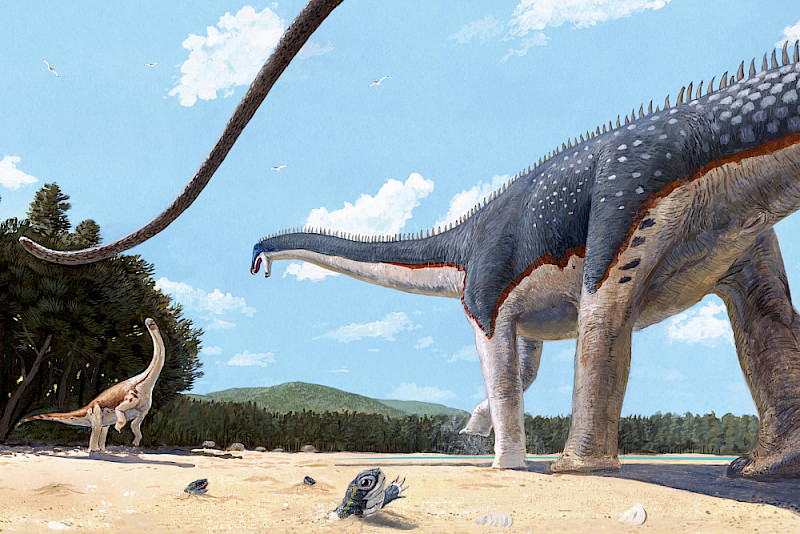

It is the story of a young dinosaur that roams with its herd 154 million years ago through what is now Northern Germany. Central Europe during the late Jurassic period is a subtropical island landscape where male saltwater crocodiles fight for the favour of females, mouse-like mammals hunt dragonflies, and where herbivores eat dwarf conifers, seaweed and marine algae. It is where the story of the young animal begins. His herd flees to safety from a predatory dinosaur only to wind up in the midst of yet another drama. During a thunderstorm, lightning nearly wipes out the entire herd and only the little one survives. And now it has to fend for itself as it searches for others of its kind accompanied by some pterosaurs, all while running away from another predatory dinosaur.

“Europasaurus – Life on Jurassic Islands” is the title of the unusual book which was released in late 2020 by the Munich-based publisher Pfeil Verlag. The results of many years of research by MLU scientist Dr Oliver Wings are depicted in a 184-page graphic novel, a form of comic strip, produced in conjunction with palaeo-artist Joschua Knüppe from Ibbenbüren (North Rhine-Westphalia) and media designer Henning Ahlers from Hanover. More specifically, it is about the work at the Langenberg limestone quarry near Goslar (Lower Saxony). A sensational find was made there in 1998: an amateur palaeontologist uncovered the bones of the first Europasaurus holgeri. The dinosaur belongs to the family of long-necked sauropods, the largest land animals of all times, some of whom grew to more than 13 metres and weighed up to 70 tonnes. Europasaurus, on the other hand, became a scientific curiosity when scientists from Bonn, Lisbon and Münchehagen (Lower Saxony) first named and described it in the scientific journal “Nature” in 2006. Contrary to initial assumptions, they were not juvenile fossils. Even when fully grown, the dinosaur only grew to a maximum height of three metres and weighed up to one tonne. Its dwarfism was probably a consequence of the limited food supply on the islands, says Wings.

Many years of experience

The palaeontologist has been working at MLU since 2017. He curates the geoscientific collections of the Natural Science Collections as well as the Geiseltal Collection, which contains 50,000 fossils from the former open-cast lignite mines southwest of Halle. It offers a glimpse into the ecosystem that existed around 45 million years ago. By then some of the dinosaurs, which Wings has been studying since his doing his doctorate at the University of Bonn, have already been extinct for over 20 million years. However, the researcher did not start with fossilised bones, but with stones from the stomachs of the prehistoric giants, whose function has not yet been fully determined. He has been gripped by dinos ever since. To date, he has conducted digs on six continents, from Greenland and South Africa to China. In the desert region of Xinjiang in northwest China, for instance, Wings found dinosaurs alongside a mass accumulation of turtles. “This was the first project in which I directly dealt with the anatomy of dinosaur bones,” says the 48-year-old. There, he and his fellow Chinese researchers also discovered the fossils of the previously unknown giant Xinjiangtitan. At 35 meters long and 40 tonnes it is one of the largest dinosaurs in the world.

Wings has also been working intensively on the prehistoric animals from the Lower Saxony limestone quarry for about ten years. “Few dinosaur species are as familiar and fully known to researchers today as the Europasaurus,” he says. A total of 21 individuals of varying ages were found in the quarry. The University of Bonn once described the area as the “Jurassic Harz”, a place that Steven Spielberg could have only dreamt of. A good 1,300 of the more than 3,000 Europasaurus bones found there have already been prepared.

According to the scientist from Halle, the finds made more than 20 years ago still provide a lot of opportunity for further research. However, they come from rubble heaps created through mining activity. About 30 metres of rock is regularly blasted to a depth of three metres in the active limestone quarry. The fossils were recovered from about 5,000 tonnes of rock, each block measuring a maximum of two metres in diameter. For the scientists, it was like a giant 3D puzzle. “We now wanted to know how the bones lay within the context of the rock,” Wings reports. Therefore, in 2011 he set out to track down the Europasaurus and its environment at Langenberg for initially five years as part of a project that received more than 600,000 euros in funding from the Volkswagen Foundation.

At lofty heights

The conditions on site, however, did not make it easy for Wings and his team. “I've excavated all over the world, but it was never as difficult as at Langenberg,” he says. One reason: the rock layers, made of former lime mud, and the remains of marine animals from the late Jurassic period are no longer horizontal but were pushed up almost vertically during the formation of the Harz Mountains. This meant the team also worked at heights of 16 to 17 metres from a crane basket using hammers and pickaxes. A total of 600 tonnes of rock were shifted and more than five tonnes washed through sieves. They initially met with moderate success - crocodile teeth and turtle shells were uncovered, but no Europasaurus. “That was a setback.”

This was followed by real success in 2014 - albeit not exactly what they had been looking for: the discovery of the first mammals from the Jurassic period in Germany. The first was Teutonodon langenbergensis, a mouse-like creature from the Multituberculata group, which became extinct about 34 million years ago. A tooth measuring only two millimetres in length was found during the preparation of another find - a crocodile vertebra. It was enough to be able identify the new species. To date, teeth from four other groups of mammals have been found. Wings explains just how unusual these finds are: “A large part of Southern Germany is covered by strata from the Jurassic period,” he says. These have been studied for around 200 years, but apart from a few terrestrial organisms washed up from other islands, only marine animals have been found. “Langenberg is the best site in Central Europe for finding new mammal genera from this period,” says Wings. In the meantime, every group of mammal that existed around the world during the late Jurassic has been detected, except for platypuses.

A new genus of small terrestrial crocodile called Knoetschkesuchus langenbergensis has also been identified. The animal was named for field work coordinator Nils Knötschke from the Open Air Dinosaur Park Museum in Münchehagen, who was also involved in Wings’ project. Two partial skeletons, several bones and many of the animal’s teeth have been found. Several partners are involved in processing the scientific finds. While dinosaur fossils - including some new fossils of Europasaurus - are being prepared at the Museum in Münchehagen, the University of Bonn is studying microfossils. Teeth can be reconstructed and a 3D image created with the help of micro-computed tomography.

The researchers have done more than just published their results in scientific journals. Oliver Wings came up with the idea of bringing the Europasaurus to life for the general public using his own research and findings from earlier projects. Many palaeontology professorships have been cancelled, partly because scientists did not put enough effort into communication, he says. They failed to explain the importance of their discipline. But palaeontology has one big advantage: “The interest is there; dinosaurs always create a way in,” says Wings.

There are many popular science books, says the palaeontologist, who himself is the author of a Brockhaus children’s book on dinosaurs which was published in 2005. This time, it was to be a more innovative form of scientific communication. He and Joschua Knüppe came up with the idea of the graphic novel, an extensive, research-based story in comic form. “At first I was worried about the amount of work the illustrator would have to do,” says Wings. But Knüppe was enthusiastic. The 28-year-old studied art and made a name for himself in science with his detailed, fact-based depiction of dinosaurs. In recent years, he has worked for several researchers and museums, and has also illustrated finds from Langenberg. “I already possessed the basic knowledge,” he says - he has been drawing dinosaurs since he was three years old. For the book, he also studied all the publications on the finds from Langenberg. One challenge, says Knüppe, was the narrative. Henning Ahlers, who has had a lot of experience in animated film design, was primarily responsible for the storytelling, readability and emotion. He also paid close attention to illustrative details in this project. “The fact that Joschua Knüppe is a paleo-artist and not just an illustrator from the advertising or publishing industry is important. In other words, he is not someone for whom science is a necessary evil,” explains Ahlers. Knüppe adds: “Muscles cannot be placed arbitrarily, nor can proportions be drawn at will.”

Three years of work

International scientists have reviewed all of the drawings and information. In addition to the pictorial history, there is a 38-page section that describes the work on the fossils in a generally understandable way. A natural event such as a lightning strike could very likely have killed the Langenberg herd as described in the book. “It must have been a sudden event that brought down all of the animals, from the babies to the eight-metre-long adults,” says Wings. If they had been poisoned, for example, the less sensitive adults would have been able to move on a ways and would not have been found there in the same place millions of years later.

A total of three years of work went into the book. “I ended up with eleven kilos of paper,” says Knüppe, who drew on sheets up to 70 centimetres wide. The project was financed with additional funds from the Volkswagen Foundation. In February 2021, a film with animated drawings from the graphic novel was also published on YouTube and three more episodes are planned. However, Oliver Wings has more research work to do at Langenberg. He has not given up hope of coming across a complete Europasaurus skeleton. “But it would almost be more exciting to find something else,” he says. A stegosaurus, for example, which so far has only been identified by a single tooth. The animals obviously lived there - but why have no other bones of theirs turned up? “It’s a question that’s been bothering me which I want to find an answer to.”

Dr Oliver Wings

Natural Science Collections

Telephone +49 345 55-26073

Mail: oliver.wings@zns.uni-halle.de