A Dialogue Between Subjects

ScienceCampus Halle (SCH) is a virtual campus because there is no geographical location, like Weinberg Campus. It is made up of four regional Leibniz institutes, the university’s faculties of Natural Sciences I and III, Agrochemischen Institut Piesteritz e. V. and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Crop Research. So it made sense that scientia halensis first stopped by its office at Betty Heimann Strasse 3. The path led past the former parade grounds of the School for Army and Air Force Signals and the greenhouses belonging to MLU’s agricultural scientists. On the ground floor of the new building we meet scientific coordinator of SCH, Dr. Claudia Flügel, in her office located at the far end of the long corridor.

“For the first time in Germany there is research cooperation being carried out between plant science, biotechnology, economic sciences and social sciences,” says Claudia Flügel. “It’s completely normal for natural scientists to be speaking another language than economic scientists. But it is precisely this that produces the greatest potential and, of course, creates a specific challenge for SCH.” In order to work successfully in an interdisciplinary fashion, subject boundaries have to be relaxed. “An intensive exchange of ideas is only possible if a willingness and a fundamental interest in the other subjects is present and if people listen to one another. It is important that the scientists are able to make their complicated topics comprehensible for an audience of laymen. It is essential to find a mutual language that can be spoken at regular meetings,” explains the coordinator. She knows that their success depends on this. In addition to her studies and doctorate in plant physiology, Claudia Flügel has just finished a distance learning degree in Scientific Marketing from TU Berlin. She sees it as her special task to act a moderator and mediator for the different subjects.

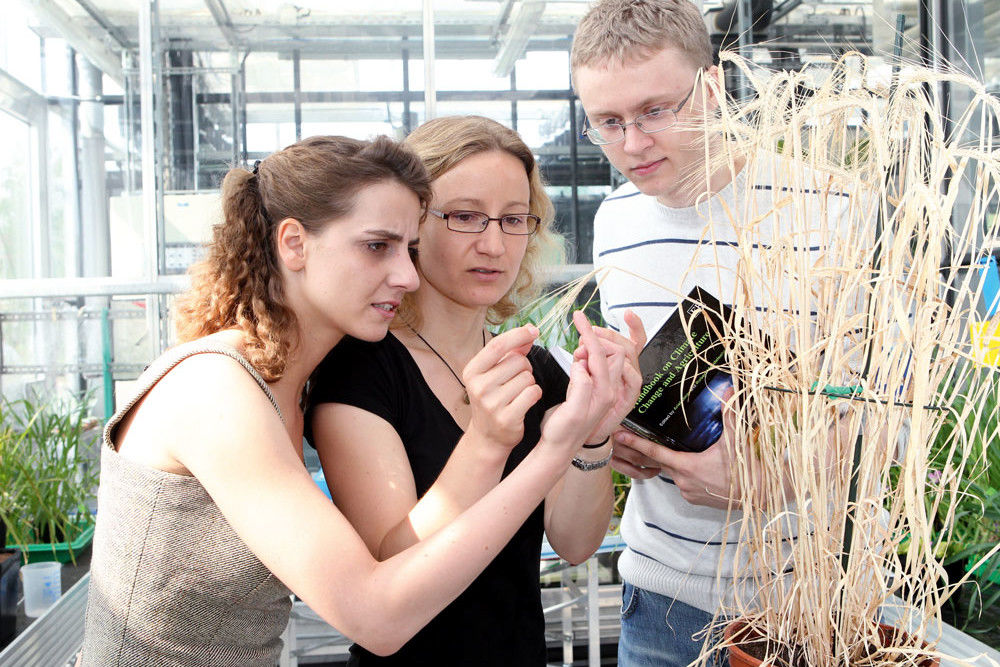

“SCH is also a platform for transferring science and technology to business, politics and the public,” Flügel explains. Here it is also essential to offer comprehensible answers to questions about plant production and the possibilities and potentials of plant-based bioeconomy. “SCH is still in its initial phase. We want to take advantage of the currently prevailing spirit of optimism and momentum in order to achieve our high aims,” says Flügel. At the moment two cross-disciplinary joint projects are running at SCH and another project is being assessed and set to begin on 1 January 2013. In addition to this, ScienceCampus is also funding a group of junior scientists at the Leibniz Institute for Plant Biochemistry. SCH wants to get young people excited about plant-based bioeconomy, a topic of the future, and to train them to be interdisciplinary skilled experts.

SCH’s network of various institutes allows it to look beyond its own horizons. As one of the first PhD candidates of ScienceCampus, economist Sven Grüner, who had just received his master’s degree in Halle, has found his research home here. “My thesis focuses on bioeconomic innovations that are looked at in the context of limited rationality and multiple targets in order to enable a policy impact assessment to be made,” says Grüner. He is following one of the two subprojects within a bioeconomic joint project on plant-based innovation and climate change. The work is being overseen by agricultural economists and MLU professors Norbert Hirschauer and Peter Wagner. Short distances between the university and the Leibniz institutes have proven to be an advantage in the initial phase as coordinating the investigation results of the different subjects is essential to the project.

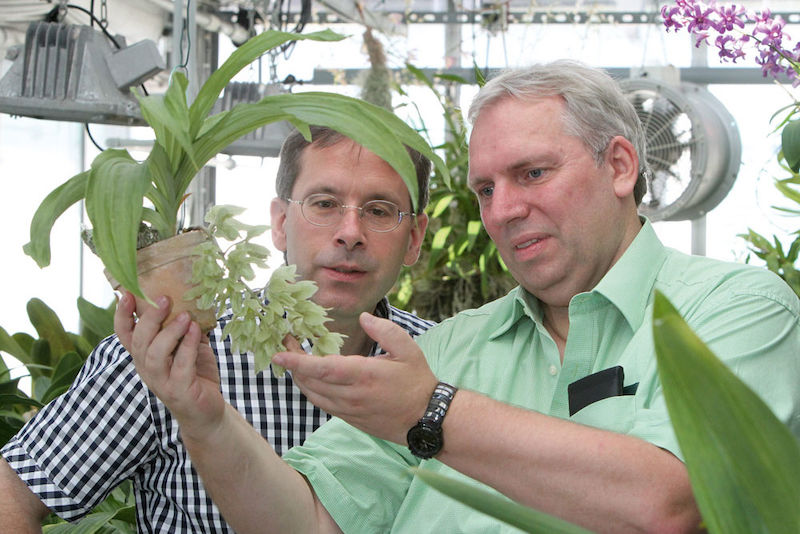

Right in the middle of summer break – at the beginning of August – both ScienceCampus spokesmen, Klaus Pillen, professor of plant breeding atMLU, and Ludger Wessjohann, professor of bioorganic chemistry and managing director of the Leibniz Institute for Plant Biochemistry (IPB), meet in a conference room at IPB in order to set out the next goals. Magnificent geraniums glow in the sun in front of the building which is situated in a park-like setting. Petunias and fuchsias are in full bloom.

“ScienceCampus is keeping its eye on urgent social problems,” says Wessjohann. “Its about the demands being made on producing plant-based products in the context of a growing world population. In order to understand things completely and to be able to highlight the many facets of a phenomenon, interdisciplinary work is an essential basic requirement. All of our food and a large part of our building materials, energy and medicines are already plant-based. This results in interactions with various technical components.” Obtaining third-party funds is the only thing that may prove difficult for SCH, Wessjohann believes. “In this area, funds are usually only granted separately to subject and interdisciplinary projects often face an uphill battle. A lot depends on the skill of the applicant.”

Professor Pillen is also of the opinion that interdisciplinary cooperation offers more opportunities than risks. He believes that SCH is currently “practicing something more like trans-disciplinary cooperation” because the research is to be integrated into a tightly interlinked process. It’s a matter of course that language barriers have to be overcome. Working together on a model in open and transparent discussion, looking at various aspects in which the levels of plant research and economy blend together, that’s how research is designed here,” Pillen explains. Not least, consumer acceptance plays a decisive role when breeding plants. “The socio-economic view is very important and was ignored greatly in the past. For example, it makes sense for plant breeders to develop a new type of wheat that contains anthocyanin, a health-promoting red coloured dye. But who wants to eat red bread?”