Do sick bees buzz differently?

Bees are quite talkative. If one worker bee wants to be cared for by another, she gives a short buzz, while queens chirp. Bees that almost bump into each other make a kind of honking sound. And even the familiar bee dance, with which workers reveal where there are food sources, is actually a song. "If we look inside the hive, we see it as a dance, but normally it is dark there", says Professor Robert Paxton from the Institute of Biology. The bees don't watch their dancing sister, but listen to the sounds she produces as she does so. "An underestimated part of the communication in the beehive runs through sounds", says Paxton.

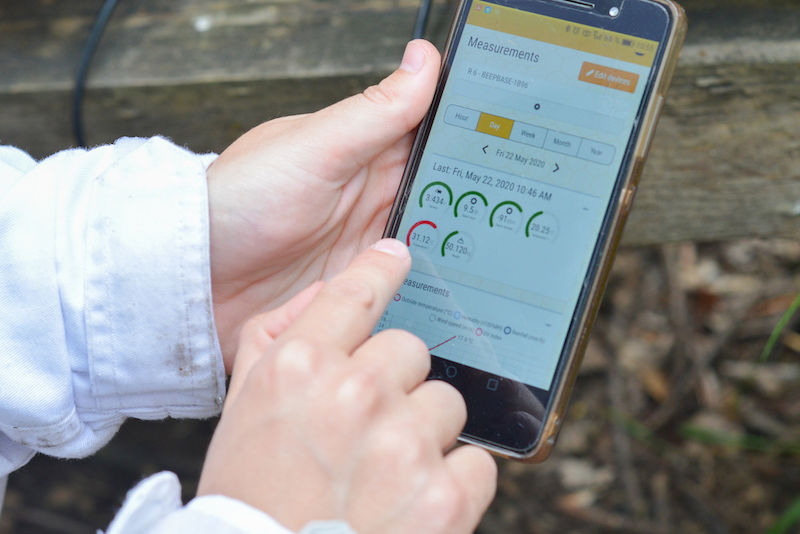

It is therefore reasonable to assume that the sounds could also tell us something about the state of a bee colony. "It's quite possible that some of them are clues to diseases or other emerging problems", says Paxton. As part of the Europe-wide research project "B-GOOD", which involves a total of 17 partners from biology, management and sociology, his research group is testing the prototype of a digital beehive. This is a metal cross with various sensors that is attached under the normal beehive and sends the collected data directly to an app on the smartphone. The sensors permanently measure the temperature as well as the weight of the hive and record the sounds from inside. The digital hive was developed by the Dutch company BEEP and is intended to enable beekeepers to monitor the condition of their bee colonies remotely at any time.

Full health monitoring

So far, however, too little is known about when bees are healthy and when they are not. "We talk about the bee colony as a kind of super organism", says Paxton. It only functions collectively and is correspondingly difficult to study. Beekeepers often only see that something is wrong when entire colonies die. The new technique must therefore first be fed with a lot of data in order to recognise new patterns. "It's about finding out definitions for healthy or problematic parameters", says Paxton. "To do that, we need to determine very precisely how the colonies are doing." In addition to the University of Halle, seven other partners spread across Europe have the new digital hives. Since spring 2020, they have all been meticulously collecting health data on the bees by hand in addition to the automatically recorded data. Tabea Streicher and Anja Tehel, PhD students at Paxton, check on them weekly. They check whether the queen is there, whether the bees are behaving normally visually and examine the infestation with varroa mites, the most dangerous bee parasite.

In addition, a so-called top photo analysis is made once a month. This means that the hive is opened and photographed from above. With the help of the photos, the number of bees is determined. Three times a year, a much more extensive analysis is carried out. Then all the frames in which the bees build their nests are taken out and measured. This makes it possible to determine exactly how many bees a colony has, how large the brood is and how much food has been collected. In addition, samples from the hive are sent to the Friedrich Loeffler Institute in Greifswald and tested for various viral, fungal and bacterial pathogens. "We feed all of this data that we record into the app", explains Streicher.

Until now, beekeepers mostly record data by hand and not on such a large scale. But the more precise the knowledge about the state of health, the more likely it is that researchers will be able to find out whether temperature, weight or sounds indicate that something is wrong with a bee colony. It is possible, for example, that bees make certain sounds when they are sick. They are also likely to become louder before they swarm, i.e. before part of the colony leaves the hive. "The goal is for the app to sound an alarm as soon as something is wrong", says Paxton. Once the research institutes are done collecting data and developing parameters, beekeepers will test whether digital hive monitoring works in practice.

Help for beekeepers

However, real-time monitoring is already showing benefits even without the alarm. For example, Streicher put the thermometer in a brood nest, the place where the bee larvae hatch. There, the temperature is kept at a constant 35 degrees Celsius – no matter how warm or cold it is outside the hive. "The nice thing is that I can now go into my app and see, in colony 8 the thermometer measures 35.6 degrees Celsius, so everything is fine there", says Streicher. If the temperature drops, the brood nest has been abandoned – that can be an indication that something is wrong there.

However, the "B-GOOD" project goes far beyond the digital monitoring of bee colonies. In another sub-project, the genetic characteristics of various subspecies of the honey bee Apis mellifera kept by the participating institutions are being studied in Halle. This should provide information on which genetic characteristics might be related to a higher resistance to pathogens, but also to a particularly good food yield.

All in all, "B-GOOD" should thus provide an overall picture of the health of the honey bee in Europe. In further projects, vegetation analyses will provide information on where the environment is particularly beneficial for bees. Management practices and socio-economic conditions for beekeeping will also be investigated. In the end, not only should the digital hive be ready for use, but so too will new, rapid tests for bee viruses and pesticide contamination of plants. The project aims to improve the conditions for healthy bee populations in Europe in the long term. "It's about supporting beekeepers in their work", says Paxton.