What remains

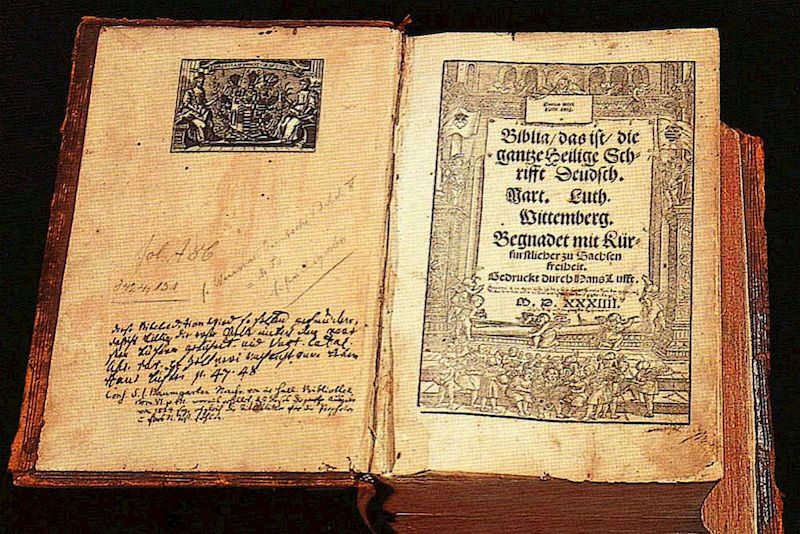

In the beginning, says Professor Hans-Joachim Solms, there is language. “It all starts with Luther’s Bible translation. It is the dawn of the modern age.” Luther’s 1545 Bible was a bestseller during the waning Middle Ages and helped to gradually develop Early High German into a supra-regional written language. “Luther gave a decisive boost to vernacular language, laying the foundations for the New High German that we speak today,” says the language historian. There had never been a standard German language.

“People found it difficult to understand others living just 30 miles away. Luther was aware of this himself. They spoke in dialect and even the written word – to the extent that there was any command of it – was regionally distinct.” It was primarily used by public officials and scholars, who very often wrote in Latin.

Scholars who widely travelled did, however, possess a “supra-regional language” which Luther capitalised on when translating the Holy Scripture into German, Solms explains. Wherever he could, the reformer chose words that could be understood across regions.

Even the printers in Wittenberg, who were the first to publish Luther’s writings, left their mark on our language. “They strove to achieve a standard form of spelling. The convention of capitalising nouns today asserted itself through its use in the Bible,” says the language historian. Solms and Professor Helmut Glück, a linguist from the University of Bamberg, are currently working on a third-party-funded project examining the extent to which Luther’s Bible translation influenced the development of Eastern European languages. Language was ultimately modelled after Luther’s Bible in broad stretches of Germany. Children learned to read and write in the spirit of the reformers, using this “Biblia Deudsch” and Luther’s catechism.

Even his church songs played a decisive role in disseminating Early New High German. “His musical poetry and scoring became an indispensable part of the Protestant hymn. From a music-history perspective, the Reformation can be regarded as the first major song movement of modern times,” says music educationalist Dr Christine Klein. “As a result, a group feeling and a common identity emerged,” adds Hans-Joachim Solms. People felt connected through the language of the Bible.

Emotional mental cinema

Solms attests to Luther’s exceptional feeling for language. “He was ingenious with language. He aligned himself with the spoken word of the people and produced a written language that was much more vivid and understandable than church texts had previously been.” In his “Open Letter on Translating”, Luther wrote about his work with language: “(..) one must ask the mother at home, the children in the streets, the common man at the market, look at their lips, how they speak, and translate based on this.”

Yet, despite this: “Luther is not the father of our language,” Solms makes plain. The reformer garnered inspiration from other Medieval authors. Today many coinages are ascribed to Martin Luther even though there is little evidence that they can be originally traced back to him.

The modernity of his centuries-old language still fascinates us. “Luther delivered visual messages in his language which enabled him to make himself and his translations discernible and perceptible. Words such as Lückenbüßer (stopgaps) and Machtwort (an authoritative intervention) appeal to our power of imagination. He emotionalises,” says Professor Steffen Leuschner who teaches media theory and media practice part-time at the University of Halle. Modern media design also strives to achieve this. “We, too, want to mobilise this mental cinema.” Above all, Luther was able to remove the veil of unintelligibility from existing conditions through his clear use of language. “You have to express yourself in a comprehensible and authentic way in order to get your ideas across. That remains true today – for example in seminars where students demand clarity,” says the professor of visual communication.

Education for all

The reformers believed that successful communication also meant that every believer should be able to study the Holy Scriptures themselves. By scripture alone – sola scriptura – the faithful could achieve their own access to God. In 1520 Luther wrote: “Shouldn’t every single Christian at age nine or ten know the Holy Gospel in which his name and his life is written?” The educational programme that he created for this purpose, together with “Germany’s teacher” Philipp Melanchthon, left an indelible mark on society.

“It is fair to say that the general idea of education in the sense of compulsory schooling has roots in the Reformation since, according to Luther’s way of thinking, every child – whether boy or girl – should learn to read the Holy Scripture,” observes religious education specialist Professor Michael Domsgen. “The reformers believed that every person could be and should be educated.” Furthermore, according to the reformers, the responsibility for education should no longer lie with the Church. Instead it should be the responsibility of secular rulers. The protestant princes developed an institutional education system, thereby laying the foundations for our general education system today.

Luther advocated for a science in which rational insight is placed above Christian dogmas. “The 95 theses were also an expression of a different understanding of science. Luther criticised the Catholic Church’s notion of science and denounced the conclusions drawn by scholasticism,” says theologian Dr Christian Senkel. After intensive study of the Bible, Luther was convinced by his own arguments; the Church was unable to provide him with any substantiated counterarguments. Moreover, he believed that the theological insight obtained by studying the Holy Scriptures superseded any earthly authority even though it was just as powerful. “[M]y conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe,” the reformer proclaimed to the emperor at the Diet of Worms in 1521.

“Luther was not the first person to develop this idea that mankind should follow his conscience before God and not before human authority,” says Michael Domsgen. “However, Luther was particularly prominent with his argumentation and actions.” Even now his remark “here I stand, I cannot do otherwise” remains unsubstantiated. Despite this, it is often cited in many languages as an expression of steadfastness and as proof of a freedom of conscience. Luther’s appearance in Worms and his refusal to act against his conscience led to his condemnation by Emperor Charles V. His writings could not be read or distributed. However, this condemnation increased demand for them even more. Soon his flyers and booklets were being printed everywhere.

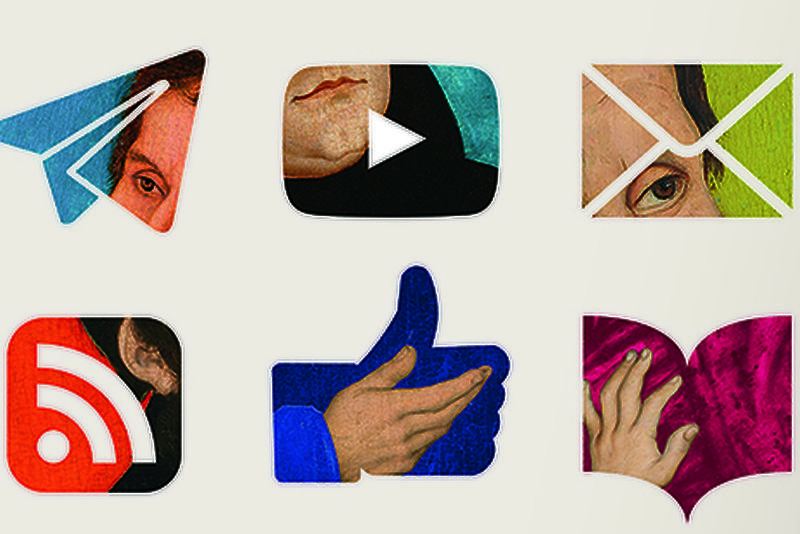

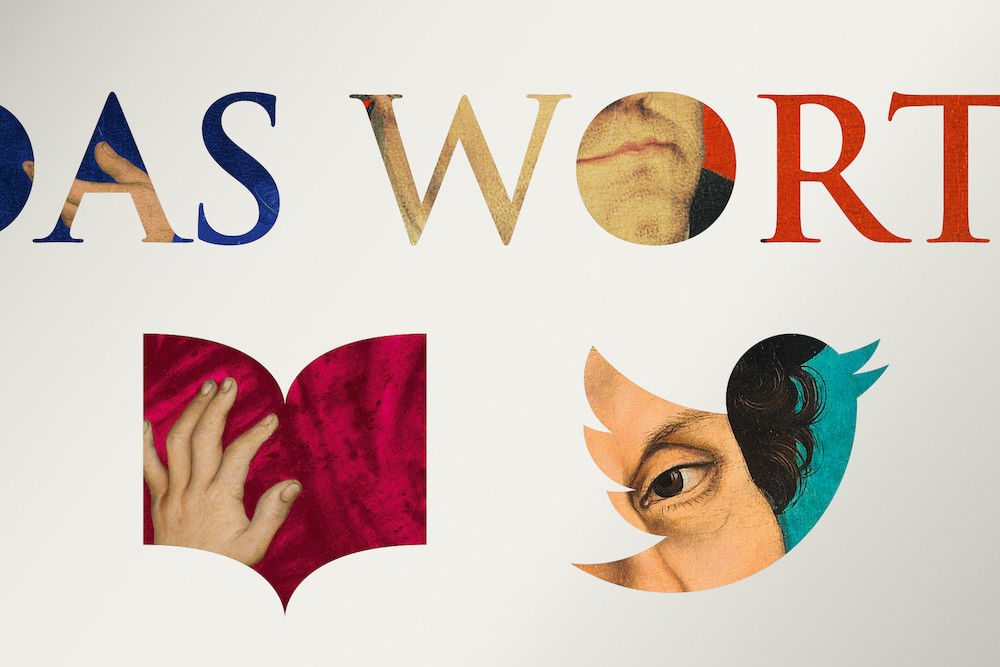

Would Luther use Twitter?

The success of the Reformation would be unthinkable without book printing, which Johann Gutenberg revolutionised through his printing press. “In the beginning, Luther distanced himself from printing – his manuscripts were primarily distributed illegally – until he realised that he could achieve more through this new form of media,” says Dr Steffi Ebert an expert in media studies. The reformer now deliberately used them for his own purposes. “Luther reduced his message to simple, individual aspects. He added illustrations from Cranach’s workshop and attached a bookplate to each of his publications which stated: ‘A change is needed!’ It is precisely such media strategies which are successful today. “When we relate this process to digital media, Donald Trump acted in a similar way during the 2016 U.S. elections,” states Ebert.

She draws many parallels between then and now from the perspective of media science. “Digitalisation means we are experiencing another media upheaval that is changing everything. With every major invention in the history of the media, society is faced with the challenge of channelling excess information. New media is always an indication that a change in values is currently taking place.” The events from back then reveal how big the challenges we are currently facing really are. “We have to find a way of making new media serve us,” says Steffi Ebert.

What would Luther do if he were alive today? The expert in media studies is convinced: “He would tweet and berate the old media.” But what would his message be on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter? He found his insight, which ultimately changed the world, in a Roman letter: Mankind no longer needs to justify himself to God through specific actions; his faith alone makes him righteous before God. A half of a millennium later this statement no longer sends shockwaves. “What concerns people today are aspects of acceptance. Mankind is in constant search of acceptance,” says religious education specialist Michael Domsgen. “Luther’s perspective might have been: acceptance also means being able to regard oneself as accepted by God. Thus we have already been accepted. This also applies to our own limitations.”