Steintor-Campus: All moved in

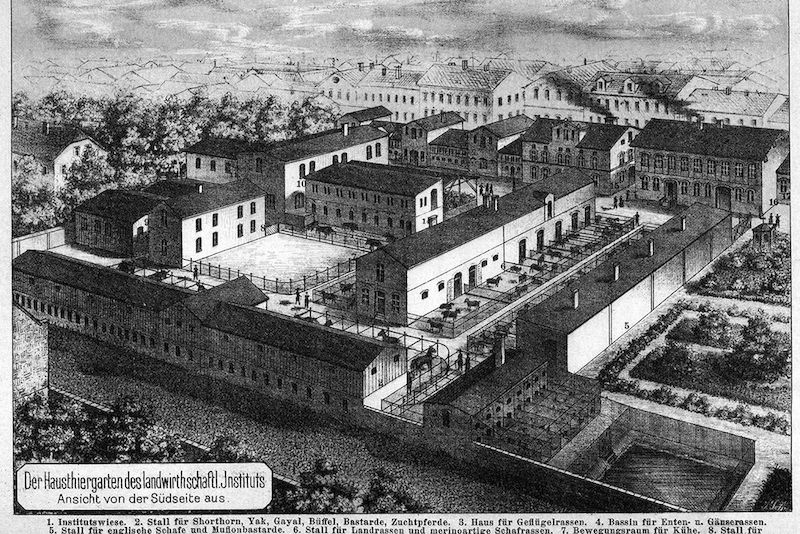

The campus from above:

Roland Östreich has a great deal of respect for the moment when classes start up on the Steintor Campus, ushering in 3,000 students in the fields of the humanities and social sciences. He has been working on site as the facility manager of the new campus since March 2015. “I am responsible for all of the buildings, but I’m also in charge of the media technology in the classrooms.” Before the start of the semester he inspected and serviced all of the technical equipment in each of the four lecture halls and in the 20 seminar rooms. Every day he pushed a wheelbarrow full of tools all over a site the size of five football pitches in order to fix the last few things and help out university staff in their 260 new offices.

Everyone has finally moved in: 350 employees from 16 different disciplines have moved to the institutional buildings with most employees working in the new white building in Emil Abderhalden Strasse. Many of the scientists used to work kilometres apart, rarely seeing colleagues from other institutes. Now they bump into each other on a daily basis: archaeologists, art historians, political scientists, Japanologists, speech scientists, Germanists, Romance scholars, sociologists, Slavists, Anglicists, philosophers, Indogermanists, historians, Classical scholars, the staff of the Institute for Oriental Studies, and psychologists.

“This proximity will gradually be reflected in the structures and at communication and organisational levels,” reports Dr. Matthias Buck, who closely accompanied the project on behalf of the Faculty of Philosophy I for five years. Students will also run into their fellow students much more frequently in the future. Students who used to have to rush from a seminar in the city centre and to a seminar in Hoher Weg for example will now be able to enjoy a proper break. Distances will also become shorter for many university staff and students.

A place where Kühn once taught using live animals

Library staff will see the biggest changes in terms of their day-to-day work. They, along with 17 different library inventories, have moved into the new and largest branch library of the University and Regional Library of Saxony-Anhalt (ULB). They now work in a building which has been called the campus’s showpiece by nearly everyone who has set foot in it. The building offers impressive architecture, modern furnishings, sophisticated technology, longer opening hours and a new catalogue system. Now you don’t have to painstakingly search for your literature in the branch libraries scattered throughout the city. The books are now located centrally on campus in a library that is open seven days a week.

During his 47 years as a professor and director of the institute, Julius Kühn created an agricultural education facility at the site of the present-day Steintor Campus that was globally without rival. He bought adjacent land, had stables built and planted a crop garden and a garden for domesticated animals that were used in teaching and research. Several trees planted at the time are now natural monuments that provide shade between Ludwig Wucherer Strasse 2 and the library. Up to 1,000 animals lived for a time on site. Several of these are now specimens at the Julius Kühn Domesticated Animal Museum. The flat, unmodernised building and the last post of the agricultural scientists on the site has been preserved. The valuable collection of domesticated animal skeletons is still being used for teaching and research.

After his death, the facilities and institutes which Kühn created were extended starting in 1910 and condensed into the Faculty of Agriculture. Four of the buildings built back then to accommodate the expanding institutes have been modernised and restored and are now part of the new campus.

One campus – many interests

On 30 October 2006 the state government passed the following resolution: The new Centre for the Humanities and Social Sciences, quickly known only as GSZ, was to be established at the site once chosen by Kühn. The project was to receive 52 million euros, three-quarters of which was to come from the European Regional Development Fund. Building work was in the hands of Saxony-Anhalt Construction and Property Management (BLSA) until the building was handed over in 2015.

In 2009 the agricultural-, nutritional and geosciences moved to the Weinberg Campus, enabling planning to get underway. The university’s Department 4 – “Construction, Property and Building Management”, urban planners, architects, experts in historical monument preservation, future users and many other people in charge worked alongside BLSA on this major project. All of the construction, modernisation and restoration work was carried out simultaneously at the university’s largest building site – a show of strength by the Building Department.

“Such a complex project needs the support and expertise of all of the units in the department. Other facilities, like the IT Service Centre, also worked closely on the project,” explains GSZ project leader, Alexander Keck, who had coordinated the project since 2012. Extensive changes were made multiple times: the old buildings in Emil Abderhalden Strasse were originally going to be modernised, however it turned out that this would cost several times more than constructing a new building. Therefore demolition work began on site in 2011. Spring 2012 saw the start of renovation work on the buildings in Adam-Kuckhoff Strasse and Ludwig Wucherer Strasse and the construction of the new institutional buildings and library. An expenditure cap meant, however, that the library had to be reduced in size.

From the time of the site selection nine years ago until the final touches were put on just recently, project managers have been sitting together every week in planning talks with experts and future users or have been visiting the building site. The requirements made by the fire brigade, the historical monument preservation board and disability representatives were continually met and finances were kept in check. “You learned more about communicating than about the thing itself,” recounts Matthias Buck, praising the university’s Building Department. “They really listened to us when it came to designing our rooms.”

Acoustic specialists listened very carefully in the newly modernised building at Adam Kuckhoff Strasse 35. Thanks to their help, the so-called presentation hall, a high, bright room, received a soundproof design. Now it not only offers ideal teaching conditions, it can also be used as a performance room by speech scientists. The new campus is also family friendly. A total of nine nappy changing stations were installed, at least one in every building. Adam Kuckhoff Strasse 34b also offers parents and children their own play and relaxation room.

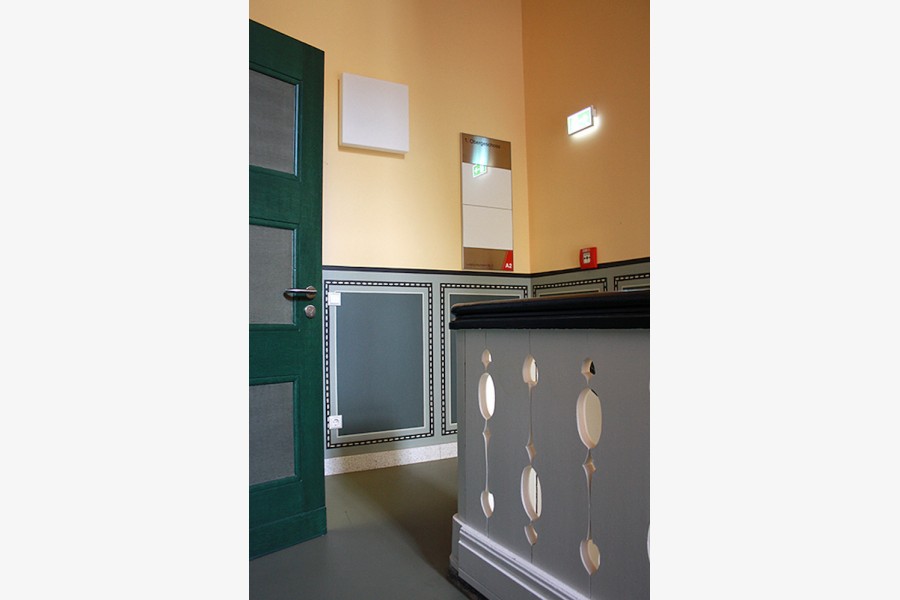

The interiors of the old buildings appear unconventionally colourful. “Restoration investigations enabled us to recreate the original colours and patterns wherever possible,” explains Alexander Keck. Apparently the agricultural scientists back then preferred colour. The walls are painted lilac, green, wine red and orange. And the original mechanically operated windows, wrought iron door handles and newly restored seating in the historic lecture halls lend the buildings their own unique character and charm.

Dr. Monika Lücke, of the Representatives for the Severely Disabled at Halle’s university, has also been heavily involved in the project since 2010. She worked five years to create a campus that is accessible to everyone. Around ten per cent of the students live with at least one health limitation. Monika Lücke represents the interests of around 300 people in the humanities and social sciences departments. The historian emphasises that everything that goes into making the campus barrier-free – from contrastive signage to wide automatic doors and handrails that one can grip around – is very important. “Every fourth work-related accident happens, for example, on the stairs. Occupational safety and protection benefit everyone.” But she has mixed reviews. “The old buildings are spacious and here we were able to achieve good results.” However she is less satisfied with the results in the new buildings.

The first members of the humanities and social sciences departments moved into the old buildings in February 2015 and into the new buildings in July. The move was finally over when the last books were placed on the shelves of the new library in September. “That was our last big move,” says Horst-Dieter Foerster, head of the Building Department, who accompanied the project throughout. It was a lot less time-consuming than the move to the Weinberg Campus. “It was primarily a move between offices. We didn’t have to transfer any ongoing trials and we only had to set up two labs.” Nevertheless the move required around 10,000 moving boxes. State-of-the-art technology now sits alongside university history.

The new institutional buildings in Emil Abderhalden Strasse, which are long and more functional-looking, house two labs for the archaeologists, a recording studio for the speech scientists, and a seminar room equipped with video conferencing for the Japanologists. Interactive whiteboards were installed in some of the classrooms and the entire campus is equipped with uni-wifi. Soon the site will also be better connected spatially as well: the Steintor Passage, which is currently being built at the southwest end of the site, will provide a direct link to Grosse Steinstrasse and the Steintor traffic junction. The new campus will leave its mark not only on the humanities and social sciences departments, but on the cityscape as well.